It began with whale sharks. When Marc A. Hayek arrived to take the helm at Blancpain, he already not only had a deep love of the ocean—born of a childhood spent watching Jacques Cousteau films and a subsequent desire to take up the sport of scuba diving—but also a particular fascination with sharks. While diving in Indonesia, he encountered whale sharks that were remarkable for their patterned markings, each as unique to the individual as fingerprints are to humans. Along with his budding interest in the species came a conviction that divers such as himself, when marshaled together, could become a vital force for preservation, not only in the places inhabited by sharks for extended periods, but also along the routes they follow between those locations.

“By establishing a protected nature preserve, where ocean wildlife could reproduce undisturbed, fishing businesses and individuals could have greater success focusing their efforts outside of the preserve”

the Pristine Seas Pitcairn expedition, which is supported by Blancpain.

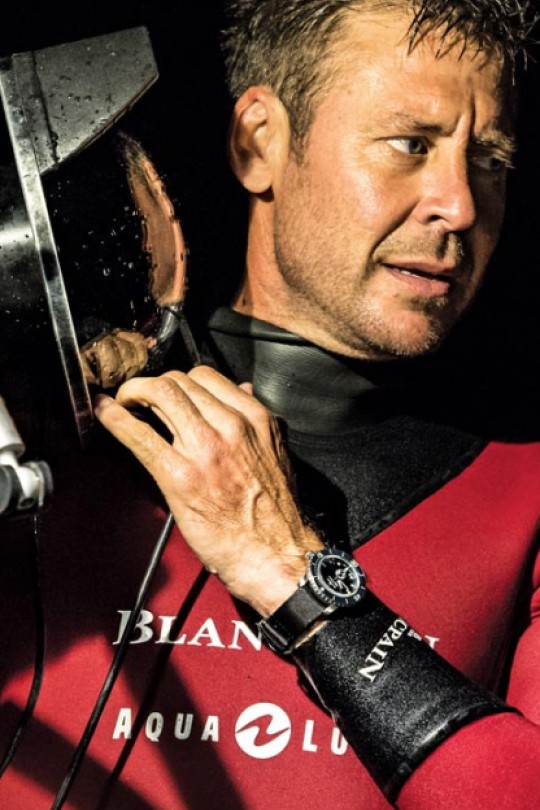

Laurent Ballesta

The 2007 launch of the new generation of Fifty Fathoms watches not only signaled a rebirth of the Fifty Fathoms collection, but also ignited Hayek’s desire to find a partner for consequential ocean projects, where Blancpain’s support could make a difference. That opportunity came from a meeting with Dr. Enric Sala, who was the founder and leader of the National Geographic Society’s Pristine Seas expeditions. Sala, in the search for funds to underwrite his project, had already approached and been turned down by many substantial business organizations. The ambitions for Pristine Seas were formidable: to study and photograph currently unspoiled areas of the ocean and, thereafter, armed with photographs and studies demonstrating the beauty and importance of the ecosystem, to approach relevant government officials to persuade them to enact environmental protection measures. As Hayek and Sala talked, one more dimension was identified. Asking political leaders to cease exploiting an ocean area was potentially costly, depriving enterprises and individuals of livelihoods dependent on fishing. Rather than merely telling leaders to issue decrees forbidding activity in the areas needing protection, Pristine Seas would present a more creative and innovative alternative. By establishing a protected nature preserve, termed a “marine protected area,” where ocean wildlife could reproduce undisturbed, those fishing businesses and individuals could have greater success focusing their efforts outside of the preserve, and the protected breeding inside the preserve, thus leading to a greater population outside. As an added plus, environmentally aware tourism within the preserve would become more attractive and successful. In short, through this approach, people would have more, not less, by protecting the ocean resource. Hayek saw this Pristine Seas “business model” as key to achieving results from the expeditions.

An aerial view of Pangatalan Island, Shark Fin Bay.

Willing to take a risk where other businesses had balked, Blancpain agreed to become the founding partner of Pristine Seas and underwrite expeditions for five years, committing $1 million USD (€910,950) per year to the project. The success of the Pristine Seas and Blancpain partnership was extraordinary. Of the fourteen expeditions ultimately supported by Blancpain, twelve resulted in governmental preservation decrees, representing a doubling of the surface area of protected ocean by over 1.8 million square miles (4.7 million square kilometers).

A whale shark.

A second important partnership arrived through serendipity. French diver, scientist, photographer, and environmentalist Laurent Ballesta visited the Basel fair in 2012, hoping to find a funding partner. To demonstrate some of his talents, he brought a portfolio of his underwater photography. By chance, Blancpain’s then vice president of marketing, Alain Delamuraz, encountered Ballesta in one of the booths, saw his impressive work, and immediately took him in tow to introduce him to Marc A. Hayek. Hayek’s agenda that day was overflowing with back-to-back meetings with nary a short interlude. Nonetheless, the two sat down to talk, with apologies in advance that the time available would be frightfully brief. After just a few minutes, the remainder of Hayek’s schedule was postponed. As the two shared their passions for the ocean, Ballesta put forward his dream. He had previously completed a deepwater dive in African waters and spotted what he believed to be a coelacanth, a prehistoric fish long thought to have become extinct centuries ago. The coelacanth has been understood to be a precursor to the emergence of marine animals adapted for life on land. Excited by the sighting, he wanted to organize a seminal expedition to study and photograph it.

Little was known about its habitat, its numbers, its evolution, its patterns of movement, or its relationship to other species. He proposed to observe the coelacanth closely, gather its DNA, tag individuals, survey its habitat, and record it all on film. A tall order, as the depths of the grottos in which coelacanths live are extreme, making the dives extraordinarily demanding. Even though Ballesta was known as a photographer, he was otherwise without backing and had never conducted expeditions of this ambition and magnitude before. Thus, there would be substantial risks for any potential financial supporter. Hayek followed his instincts, immediately grasping Ballesta’s talents and dedication. The result: Blancpain agreed to fund Ballesta’s coelacanth expedition, which he had named “Gombessa,” the name for the coelacanth used in Mozambique and Comoros.

Laurent Ballesta during the Gombessa 3 expedition to Antarctica.

Blancpain’s relationship with Ballesta has blossomed into many subsequent expeditions, all bearing the Gombessa name. His scientific research has been groundbreaking and truly important. More impactful for the general public have been his photographs and films, which have been seen by millions. Indeed, Ballesta received the prestigious Wildlife Photographer of the Year award from the Natural History Museum in London for his work in 2021—an accolade accompanied by two additional Wildlife Photographer of the Year honors in 2017 and 2022, as well as several other film awards. There are those who champion environmental causes by showing the horror of destruction. Ballesta and Hayek believe the opposite; theirs is a positive message. It is more powerful and inspirational to let people discover the wonder and beauty of the ocean and, from that, find the motivation to act.

Photo from the Pitcairn Pristine Seas expedition.

As Blancpain’s ocean-oriented environmental campaigns grew in scope and importance, Blancpain sought to embrace what were individual initiatives under a larger whole. The umbrella name for its ocean preservation efforts came to be known as the “Blancpain Ocean Commitment.” Not only did the Ocean Commitment signal Blancpain’s devotion to the cause, Blancpain also enlisted dedicated personnel whose sole job function would be to oversee management of the relationships with partners such as Pristine Seas and Ballesta and to identify other worthy partners.

The business model that Pristine Seas and Blancpain used so successfully in the past has now been reemployed in the Philippines. One of the islands in Shark Fin Bay was essentially devastated by dynamite fishing in the past. This disastrous and wasteful method employs explosives detonated in the water to kill fish in the area so that they can be amassed with nets. In a short period of time, virtually all marine life is extinguished. Today, the area around the island has been restored, with life now returning but remaining under threat from fishermen working in neighboring areas. Blancpain has partnered with the Sulubaaï Environmental Foundation to educate and persuade local villagers to adopt new methods of interacting with their environment. As was the case with Pristine Seas, this involves training them in innovative ways to restore the surrounding area and demonstrating that by creating preserves that allow marine life to safely reproduce, fishing outside of those areas using conventional methods can be more productive. Environmental protection delivers more, not less.

Blancpain’s Ocean Commitment is certainly not static. To the contrary, it is ever-evolving as new environmental dangers and partners present themselves. However, there is one constant: Blancpain’s determination to make a difference.