Mountains can be good teachers. Throughout our history as a species, we have turned to mountainous landscapes in search of meaning. Ancient scholars retired in rumination to mountaintop monasteries, perhaps drawn to the mountain’s neutrality, quiet, and stillness. Yet others entered and rose into mountainous habitats seeking solitude and anonymity, in pursuit of those intangible revelations in nature that are so grand as to eclipse the relative smallness of the human experience. Alas, mountains invite humility.

“Things are themselves only as they belong to something more than themselves: I to we, we to earth, earth to planet and stars, countless stars more themselves mirrored in the eye for a moment and then vanishing there, forgotten completely and leaving room to spare for whatever occurs next.”

To lose oneself in a mountain landscape is vital to its appreciation; one must look outward—at perilous trails, dangerous switchbacks, roads worn nearly invisible with time—to progress upward toward the summit. On mountainous excursions, to forget one’s own preoccupations and to instead pay attention to one’s surroundings is to protect oneself.

Les Pavots vineyard was first planted in the early ’80s and has since undergone gradual redevelopment as experience and climate inform how to continually capture the terroir.

The Wappo people inhabited the environs surrounding Mount Saint Helena for millennia before European settlers arrived. The Wappo people anointed the mountain with its true name: Kanamota, which means “human mountain.” They expressed their reverence for Kanamota by caretaking its natural environs, including controlling the underbrush to prevent disastrous fires. In the mid-1700s, there were upward of sixteen hundred Wappo tribe members living in and around what is today known as Calistoga and the surrounding area. By 1841, Mount Saint Helena had received its “official” name, granted by an officer named Alexander G. Rotchev, who was stationed at the time at Fort Ross. He named it for his wife, the Russian princess Elena Pavlovna Gagarina. Vestiges of a plaque honoring her can still be found at the summit.

As the vineyards reach elevations of 2,000 feet (610 m), oftentimes riding horseback provides an alternative to walking the steep slopes of the Knights Valley ranch.

Throughout the seasons and from day to night, the estate shows its evolution while retaining its natural beauty.

People come and go, but the mountain remains.

On a clear day, one can see the outline of the San Francisco skyline in grayscale from Mount Saint Helena’s summit, and even further beyond, 194 miles (312 km) away, the impression of Mount Shasta floats off in the distance like an apparition. While Mount Saint Helena, emblematic of wine country, can be viewed from Sonoma, Napa, and Lake Counties and touches all three, it is lesser known than Diamond Mountain, Atlas Peak, Mount Veeder, Spring Mountain, and Howell Mountain. While it is equally as simpatico to the vine as the other peaks, it is not as hidden; it is more easily identified and viewed, and for this reason, perhaps we’ve grown accustomed to its majesty.

Unlike the Napa Valley, just miles to the south, Knights Valley remains a highly coveted region, isolated from growth and population and offering expansive vistas.

Mountain soils are often volcanic in nature. Volcanic soils are thin and lack a permanent water table, allowing winegrowers to apply appropriate water deficits to limit vegetal growth and to encourage the development of small, intensely concentrated berries with higher color concentration and skin-to-juice ratios. Wines from mountainous regions—the Santa Cruz Mountains, El Dorado, Napa Valley, and Knights Valley—when thoughtfully farmed and made, often possess great tension and energy. These characteristics, in tandem with robust-yet-finessed tannins, often result in age-worthy wines of great depth of character. Mountain fruit is often coveted for these paradigmatic characteristics, and wine enthusiasts eventually discover and relish wines made from upland fruit. Many of California’s most-collected wines originated in mountainous vineyards. Ridge. Diamond Creek. Mayacamas. Even their names bow to the landscape that made them.

“Many of California’s most-collected wines originated in mountainous vineyards.”

The Peter Michael Winery and estate vineyard, in the Knights Valley appellation, unfolds on the slopes of Mount Saint Helena, on one of its “summits of Sonoma,” called Sugarloaf Hill. And, while we describe the soils of Mount Saint Helena as volcanic in origin, Mount Saint Helena itself is not a volcano. It is, rather, the result of the Sonoma Volcanics, several different volcanos in the Napa-Sonoma region that erupted between three to eight million years ago. Mount Saint Helena is a caldera: a large depression that forms in the earth when a volcano collapses into the cavity once occupied by erupted magma. The Petrified Forest in nearby Calistoga is a result of the same Sonoma Volcanics event that created Mount Saint Helena. The Sonoma Volcanics led to the formation of gold and silver deposits on Mount Saint Helena, which ushered in a robust era for miners. Though silver and mercury mines drew many miners to Mount Saint Helena, by 1880, most of the mines had shut down. While researching the history of mining on Mount Saint Helena, I spoke to Herb Westfall, Peter Michael Winery’s estate manager. I learned that in the late 1960s, Herb’s father established the Western Mine on Mount Saint Helena.

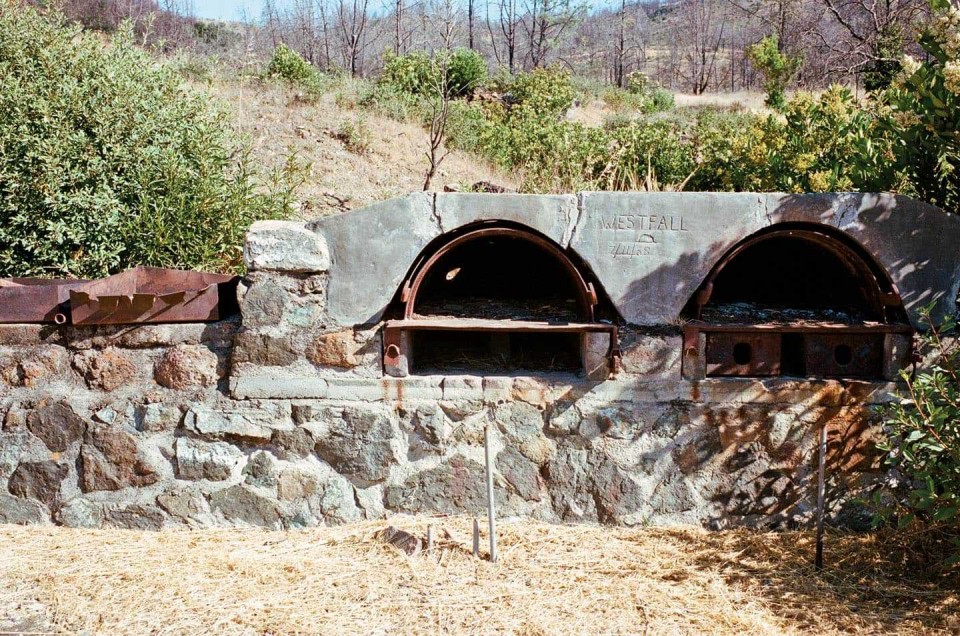

For over twenty years, estate manager Herb Westfall has tended to the estate. Westfall grew up next door to the ranch, and his family mined the estate in the 1800s. Remnants of the equipment used to mine cinnabar are still visible today.

Regardless of the location on the ranch, Mount Saint Helena towers over the vineyards.

Ida Clayton Road, which runs along the estate vineyards, becomes known as Western Mine Road, once it crosses over to the Lake County side of Mount Saint Helena. It was off Western Mine Road that Herb’s father and an associate began mining for mercury in Knights Valley in 1967. They mined successfully for two or three years before mercury prices plunged, and the mine became untenable. Today, remnants of the Western Mine remain; the openings to the mine shaft resemble a pizza oven. Mercury is mined from cinnabar and has many uses, from vapor lights to thermometers. In the gold rush days, mercury was mined on Mount Saint Helena to aid in the extraction of gold from other minerals and sediments.

“The Knights Valley vineyards are underlain by rhyolite,” says Robert Fiore, winemaker at Peter Michael Winery. Rhyolite is “the most explosive form of volcanic rock…what makes one volcanic rock more explosive than another? In this case, the amount of silica controls the viscosity of the lava. Higher silica content means higher viscosity and therefore less opportunity for gases to escape. Those pent-up gases build pressure, like carbon dioxide in a bottle of Champagne, and eventually cause the volcano to violently explode. This is the phenomenon mainly responsible for the character of the ground beneath the Knights Valley Estate vineyards. Much of the Belle Côte, La Carrière, Ma Belle-Fille, and Mon Plaisir vineyards feature rocks deposited approximately three million years ago when a gaseous cloud of pumice and ash came to rest, forming a layer of white rock known as rhyolitic ash-flow tuff.”

Over the years, I’ve come to understand specific terroirs by immersing myself in them. And so it was that in my early twenties, I began climbing Mount Saint Helena rather regularly. To explore the wild, untamed milieu of this mountainous upland is to better understand the wines that are born there. Today, when I hike Mount Saint Helena, I’ll do so with a bottle in tow, with the intention of understanding its provenance more intimately. If you are so inclined to enjoy a similar pursuit, dear reader, I invite you to join me.

Though it stands at 4,341 feet (1,323 m) at its highest peak, the trailhead to the summit begins at just over 2,000 feet (610 m), so by the time you’ve parked your car, crossed both lanes of Highway 29, and entered the Robert Louis Stevenson State Park, you’re already about halfway to the top! It’s a relatively easy trailhead to find, and the Robert Louis Stevenson Park is about nine miles (14 km) north of the town of Calistoga.

Robert Louis Stevenson, for whom the park is named, spent his honeymoon on Mount Saint Helena in an abandoned mine camp in 1880.

Around 1987, Fanny first met Robert Louis Stevenson while living in France. But it wasn’t until 1879 that they reconnected in Monterey, California, and married in San Francisco in 1880.

His wife, Frances “Fanny” Van de Grift Osbourne, brought her son Lloyd with them, and the three of them claimed the abandoned campsite for the entirety of the couple’s honeymoon. Stevenson, perhaps best known for having written Treasure Island and the Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, wrote The Silverado Squatters about his time on Mount Saint Helena, and some of the book was composed there:

Those lodes and pockets of earth, more precious than the precious ores, that yield inimitable fragrance and soft fire; those virtuous Bonanzas, where the soil has sublimated under sun and stars to something finer, and the wine is bottled poetry: these still lie undiscovered; chaparral conceals, thicket embowers them; the miner chips the rock and wanders farther, and the grizzly muses undisturbed. But there they bide their hour, awaiting their Columbus; and nature nurses and prepares them. The smack of Californian earth shall linger on the palate of your grandson.

A solid brass plaque honoring Stevenson can be found about a mile (1.6 km) up the trailhead. Further on up, the trail widens and becomes a fire road for the remainder of the ascent. The journey to the summit and back is a ten-mile (16-km), round-trip hike. In my youth, it took me three hours to reach the summit. These days, it’s closer to four hours. For that reason, it’s not advisable that one makes this hike in the summer. Spring and fall are the ideal seasons to explore Mount Saint Helena, bearing in mind that it’s wise, even in cooler weather, to begin the hike earlier in the day.

“Stevenson was perhaps the first major literary figure to write about terroir.”

Typically, I’ll begin my hike up Mount Saint Helena around 7:00 a.m. There are no benches or bathrooms at the park, and though there is much tree life on the way up, the last mile or so is mostly chaparral and shrubland. Shade becomes rarer toward the summit, and so a hat and layered clothing is recommended.

With over 600 acres (243 hectares) unplanted and preserved for wildlife, the Michael family’s commitment to land stewardship is reflected in their sustainability certifications.

On the path to the fire road, you’ll wind your way through heavily forested trails; a mix of Sierran conifers, including white fir, Douglas fir, ponderosa pine, sugar pine, incense cedar, and California black oak. The fragrance of the tree life alone is heady; if there’s a breeze that day, a sharp pine and rich bark scent will accompany you all the way to the top of the mountain. After rain, the strong smell of petrichor freshens the air. Near one of the mountain’s creeks or small waterfalls, you may spy a western pond turtle. Up above, or alighting in the forest canopy, is a generous array of birdlife.

If you’re an avid birder like I am, you’ll want to keep an eye out for golden eagles and ospreys. These magnificent, regal birds can be seen more readily as one reaches the summit. On the way up, though, you may see purple martins, tree swallows, and song sparrows. Chapparal lilies and other wildflowers punctuate the forest floor with bright hues of pink, yellow, and white. Perhaps because the entire park is under conservation, it becomes obvious to the hiker early in the trek that wildlife thrives in this mountain habitat. Bears, cougars, bobcats, and mountain lions are also frequently spotted on Mount Saint Helena, though I’ve never seen one myself.

The creek beds are cleared to maintain proper exposure for wildlife. Each estate carries the Fish Friendly Farming Certification.

I’ve long preferred tasting wine outside, especially if I’m trying to understand and appreciate a wine for the first time. On a cool, brisk day, when the wine being tasted is also cool and fresh, the sensation of smelling a wine in the wild can be transcendent, and drinking a wine where it was born gives one a real sense of terroir.

While geothermal activity shaped much of this region, throughout history, both Lake County and Calistoga have also been a destination for tourists to experience the relaxation and health benefits the pools offer.

I hike with a backpack holding a canteen of water, a couple of protein bars, sunscreen, a blanket, and, if I’m hiking through a wine region, a bottle of wine that finds its origin there. When I’ve reached the summit of Mount Saint Helena, I’ll set down my backpack and take in the view. I don’t mind reaching the summit when visibility is low. Fog and clouds obscuring the view can invite the mind to imagine it is a part of the firmament. It’s calming to be on the top of a mountain, even if one can’t see anything below. On a clear day, though, I look forward to seeing the San Francisco Bay and Mount Tamalpais. The Geysers complex, one of the largest geothermal fields in the world, is also visible, as are the twenty-two geothermal power plants that comprise it. The energy generated from these geysers helps to power Sonoma, Mendocino, and Lake Counties, as well as parts of Napa and Marin Counties. These power plants draw steam from about 350 wells. Long before these geothermal plants were conceived, the Wappo people and other indigenous peoples built steam baths from these geysers and used the steam for cooking, healing, and ceremonial purposes.

“At its very core, the essence of terroir is life itself; teeming as it is with a multitude of influences, many of which the human eye cannot even conceive.”

When I arrive at the summit, I typically meditate for a half hour or so, and I’ll stretch too before unpacking and opening the wine. I’m especially fond of trying mountain-sourced Cabernet Sauvignon while I’m hiking Mount Saint Helena. The aromatic lift of a well-made, elegant, finessed Cabernet Sauvignon as it meets the smell of mountain dust, chaparral, wild sage, and the bark of a thousand trees results in an experience as gratifying and exciting as live theater or an immersive museum visit. When the bouquet of a wine echoes the aromatics of the natural environment in which it is being consumed, new elements can be found in the glass. Was that a saline breeze just then? And was that from potassium in the soil? A coastal breeze from far, far away that made its way up the summit? Dampness on volcanic dust? Is that a hint of pine? Creosote? Do I smell the down of dewy feathers? Are there birds nearby?

Terroir existed before wines ever did. Terroir is the language of a place. It is the totality of all the natural elements that comprise it; the animal, plant, human, and ambient lives that compose a natural environment. At its very core, the essence of terroir is life itself; teeming as it is with a multitude of influences, many of which the human eye cannot even conceive. So it is that breath becomes integral to the appreciation of terroir. Taking deep, plentiful breaths invites a plethora of memory-fueled sensations, and those come to bear upon the enjoyment inherent in tasting wine outdoors.

Descending Mount Saint Helena is even more pleasurable than the ascent; on a pleasant-weather day, there’s a gentle wind at one’s back. While today the Napa Valley is known mostly for its luxurious wines, world-class accommodations, and fine restaurants, the very heart of the valley is still in the same place it was when Stevenson visited:

Napa Valley has been long a seat of the wine-growing industry. It did not here begin, as it does too often, in the low valley lands along the river, but took at once to the rough foothills, where alone it can expect to prosper. A basking inclination and stones, which serve as a reservoir of the day’s heat, seem necessary to the soil for wine; the grossness of the earth must be evaporated, its marrow daily melted and refined for ages; until at length these clods that break below our footing, and to the eye appear but common earth, are truly and to the perceiving mind, a masterpiece of nature.

snapshot into the history of geologic activity and climate are documented in the layers shown in the trees and rock formations.

Budwood for the vineyard is skillfully selected and planted based on many factors, one being the soil profile.