California’s State Route 1, more commonly known as the Pacific Coast Highway, hugs the entire coastline of the Golden State. Considered one of the most visually stunning highways in the United States, millions of travelers from around the world drive its circuitous twists and turns annually, windows rolled down, taking in the Pacific’s saline breezes and a dramatic, singular coastal landscape.

Passing through Big Sur, the air is heavy with the warm bark and sharp needle fragrance of Pinus radiata, the Monterey pine, a species native to the Central Coast of California. One can almost imagine novelists Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin, who both lived in Big Sur well into their twilight years, breathing in the sunset at day’s end.

Farther north, with San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge in the rearview mirror, the ocean cools dramatically, and jagged cliff walls emerge, towering above crashing waves below. The climate becomes less hospitable; heavy fog and damp mists a territorial signature. Along this stretch of the Pacific Coast Highway, 11 miles (18 kilometers) north of Jenner, and just south of Fort Bragg, is Fort Ross, home of the Seaview Estate and of Fort Ross State Historic Park, site of a once vibrant Russian colony.

This small, unadorned chapel was the first Russian Orthodox church in California and served as a place of worship and education for the colonists and natives.

The “Ross Colony” (from the word Rossiia, meaning “Imperial Russia”) was founded in the early 1800s and lasted only three decades, but its ghostly shadows remain, integral to the story of early California. The former Russian colony, the remains of which can be visited at the state park, has a melancholy, solitary aura. There’s something plaintive hanging in the air there, especially at the old Russian Orthodox cemetery, where Russian women, men, and children were buried alongside their fellow indigenous Coast Miwok, Pomo, Aleut, and Kashaya villagers.

During its three decades, the Russian settlement proved to be one of the more harmonious environments for indigenous peoples, where they commonly wed Russian villagers and birthed what were then called “Creole” children. It is said the two cultures lived in relative harmony, unlike the tension that existed between indigenous peoples and Spanish colonizers.

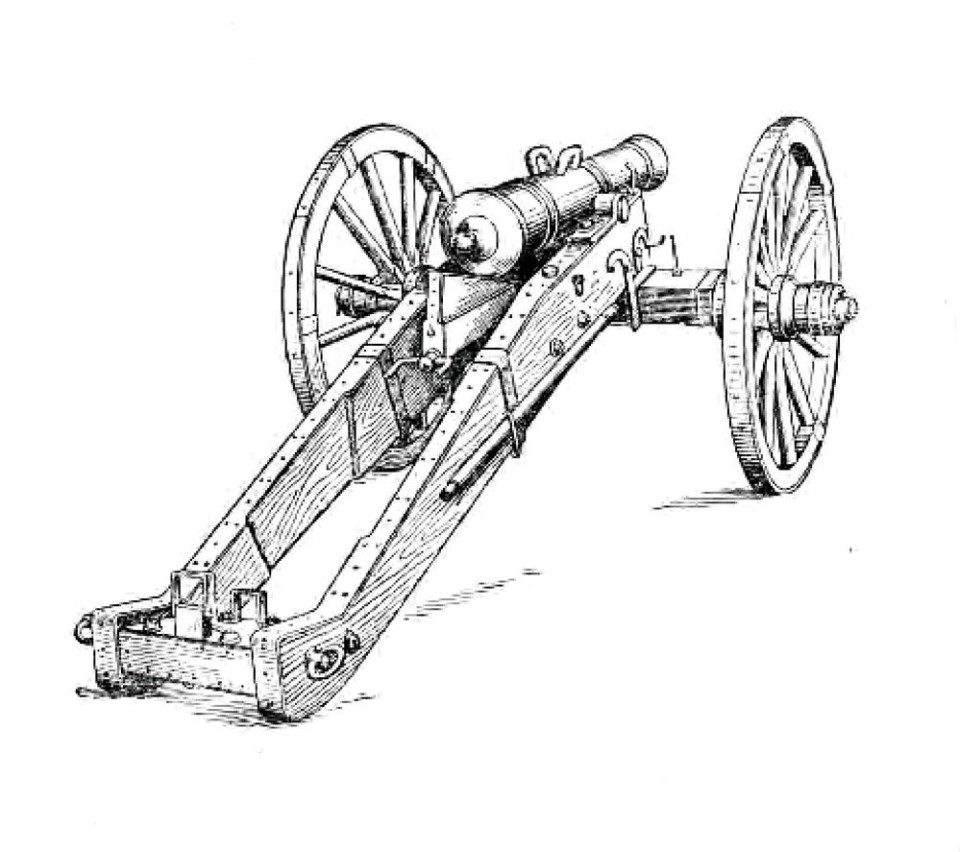

Though it looks like a military installation, there was never any warfare at Fort Ross. Instead, colonizers, under the direction of czar Peter the Great, established the community in the early 1800s after life in Alaska proved too difficult. Severe weather, a lack of nutritious food, and a nearly depleted otter population—a mainstay for Russian fur trappers—drove Russian colonists toward what is now the Jenner coastline.

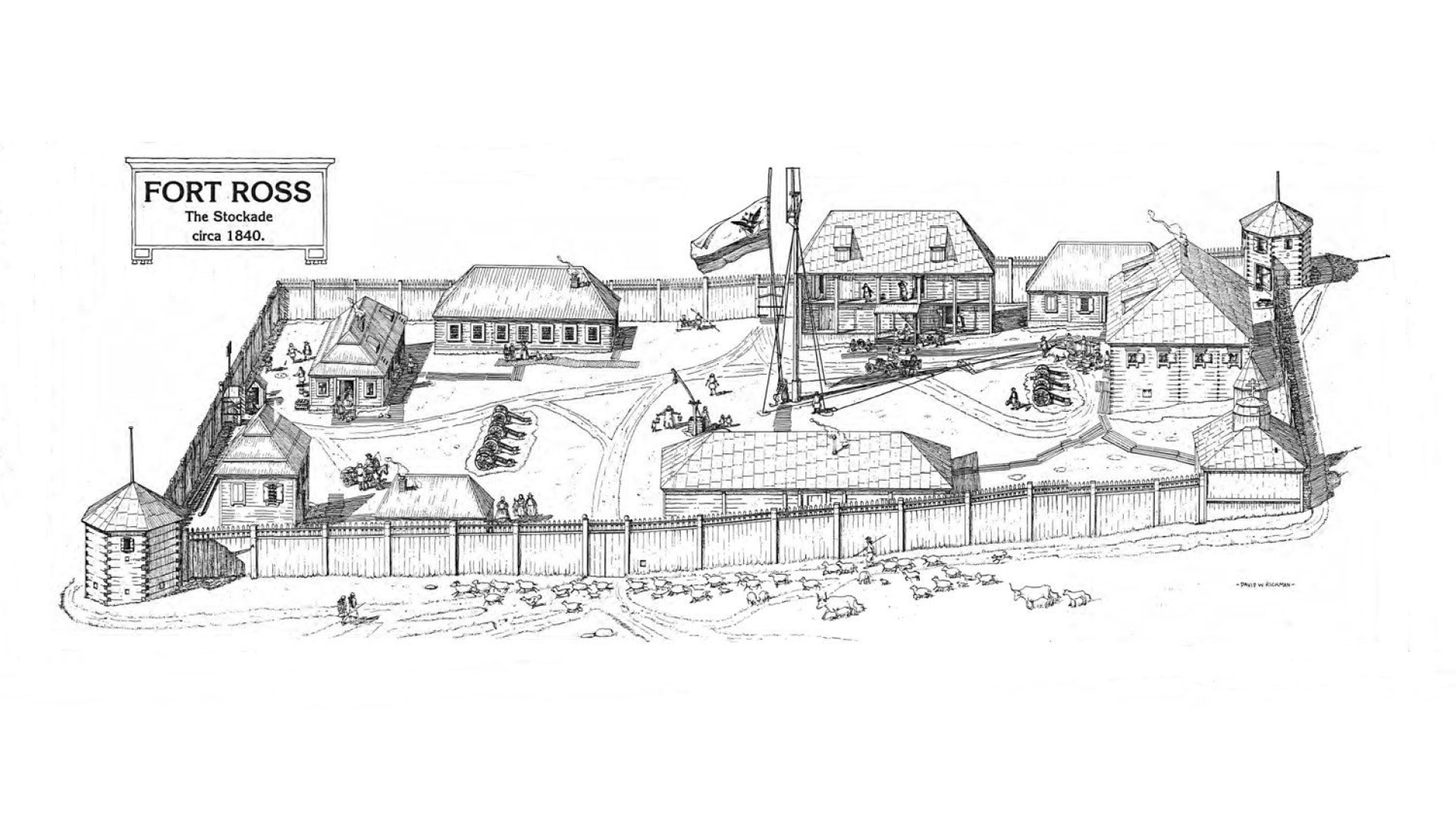

Inside the stockade, there were several buildings, including a chapel, officers’ quarters, the barracks (above).

The Rotchev House was the home of the last manager of Fort Ross, Alexander Rotchev. Originally a one-story, single-family dwelling, it is the only original building from the Russian era that still stands today.

The site was established in 1811, atop a promontory up the coast from Port Rumiantsev (now known as Bodega Bay). Timber and a dependable water supply made this an attractive location, and in 1812, settlement building commenced, with the addition of a stockade, bell tower, two windmills, cattle yard, farm buildings, bathhouses, two blockhouses, two threshing floors, a home for the governor, a forge, a tannery, and a Russian Orthodox chapel dedicated to Saint Nicholas. Along the cove below, a small shipyard and boathouse were erected. Most everything was made of redwood.

Under the supervision of a Russian foreman, native Californians and Aleuts from Alaska, who lived in earthen huts on the outskirts of the colony, regularly embarked, alongside Russian colonists, on arduous harpooning expeditions at sea. They’d return with an abundance of seal and sea otter pelts; salmon, sea perch, and sea bass; and bird meat, eggs, and feathers, as well as salted sea lion meat and kegs of whale blubber, used for food preparation and lamp oil. The ocean proved more abundant than the land, where crops were never plentiful. It was too cold and moist for wheat to properly thrive. And though cattle were raised, grazing was limited due to harsh maritime conditions.

The stockade had two gates, one facing the ocean and one facing inland, and four corner blockhouses that served as lookout towers and defense posts.

In the summer of 1836, Father Ioann Veniaminov, a Russian Orthodox priest, arrived from Alaska to facilitate weddings, confessions, communion services, baptisms, prayer services, and burials. In 1990, to better understand the composition of the historic Russian cemetery, the University of Wisconsin, in tandem with California State Parks, excavated the cemetery where Orthodox and Native graves were unearthed. Artifacts like buttons, crosses, religious medals, beads, and fragments of clothing were unearthed. Later reinterred, the remains were given last rites and blessed by a Russian Orthodox priest. Among the buried were twenty-nine people who died of measles and dysentery, seventeen people from unknown causes, and six “unnamed” deaths. The buried included three Creole families, seventeen Aleut males and eight Aleut females, Russian men and women, numerous children who were the offspring of Indigenous Alaskan and California women and men, and Russian colonizers. Many years later, Father Ioann Veniaminov was canonized, becoming Saint Innocent of Alaska.

In 1839, officials of the Russian government decided to close and abandon the colony. The sea otter population had been depleted, and expectations for a vibrant grain, beef, and dairy industry could not be met. Shipbuilding was difficult and proved largely defective, with manufactured goods not returning enough profit to offset costs. Moreover, Russian claims to the territory were challenged by the new Mexican republic, and eventually, the colony proved untenable.

By 1842, the colony had been completely abandoned. Alexander Rotchev, who would become the final manager of Fort Ross, went on to work the Gold Rush in 1851. He invented and obtained a patent for the first gold-washing machine in California. It was set up in the Yuba River area.

The coniferous coastal cypress, found along the Sonoma coastline, is shaped by the winds.

Peter Kostromitinov, who’d also been a manager at Fort Ross, ended up in San Francisco, where he distinguished himself as the Russian vice council, a position he held until 1862. Other displaced Russian colonists formed the Kodiak Ice Company, successfully cutting and storing ice that supplied most of San Francisco. Unfolding over 3,400 acres (1,376 hectares), Fort Ross is still perhaps best known for the Saint Nicholas chapel. Though the original chapel was destroyed in the 1906 earthquake, it was rebuilt between 1915 and 1917. In the autumn of 1970, an accidental fire ripped through the chapel, destroying it once again. By 1973, it had been reconstructed using lumber from the burned remains, a Russian Orthodox tradition. The original chapel bell melted in the fire, so a new one was cast in Belgium using rubbing and metal from the original bell. Russian Orthodox services are still offered there on Memorial Day, Fourth of July, and during the annual Fort Ross Festival in July. Two small inscriptions appear on the bell today: “Heavenly King, receive all, who glorify Him.” And, along the lower edge, an inscription reads, “Cast at the foundry of Michael Makar Stukolkin, master founder and merchant at the city of St. Petersburg.”

Below Fort Ross, Sandy Beach Cove, the former Russian port, now draws fishermen from around the Bay Area who enjoy the ample rock fishing the area provides. Tide pools teeming with aquatic life are popular among families and schoolchildren on field trips to the region. History buffs are also drawn to the Fort Ross Center, where numerous artifacts from the SS Pomona are on display. Submerged in 1908 after striking huge rocks off the Fort Ross coast, remnants of the SS Pomona remain submerged off the coastline. In 2019, a Sonoma County diver, John Harreld, shared footage of his dive to the Pomona with the Sonoma Coast Historic and Undersea Nautical Research Society, which can be viewed at the center.

“Unfolding over 3,400 acres (1,376 hectares), Fort Ross is still perhaps best known for the Saint Nicholas chapel.”

Originally constructed in the mid-1820s, the chapel was rebuilt following the 1906 earthquake and again in 1973, following a fire.

Just up the road from the old Ross Colony, on Fort Ross Road, is the historic Fort Ross orchard. Open to guests, the orchard was first established in 1814 with a single peach tree. Next, grapes were planted and then came apples, cherries, bergamot, quince, and pear trees. The overture of establishing an orchard was intentional: the fruit was intended to help prevent scurvy, which was adversely affecting the health and lifestyle of colonists and indigenous people alike. Today, a Capulin cherry tree, planted in 1820, is one of the few remaining trees from that time. Pear, apple, and olive trees abound throughout the orchard today, providing a shady, pleasant walk-through for visitors.

Although it is thousands of miles from the motherland, for many of California’s Russian Americans, Fort Ross provides a nostalgic and necessary link to their ancestral soil.

An exterior view of the fort.

The most profitable industry run by the Russians in California was hunting sea otters for their pelts, which needed to be treated and prepared at the Fort Ross tannery before they could be shipped back to Russia or traded with the Spanish. The tanners used lime from seashells and tannin from oak bark in the area and, in addition to sea otters, also prepared cowhides, deer hides, sealskins, wild goat skins, and sea lion skins. The goods made from these hides included shoes, leather, and deer hide suede. From The Khlebnikov Archive—Unpublished Journal (1800–1837) & Travel Notes (1820, 1822, & 1824).