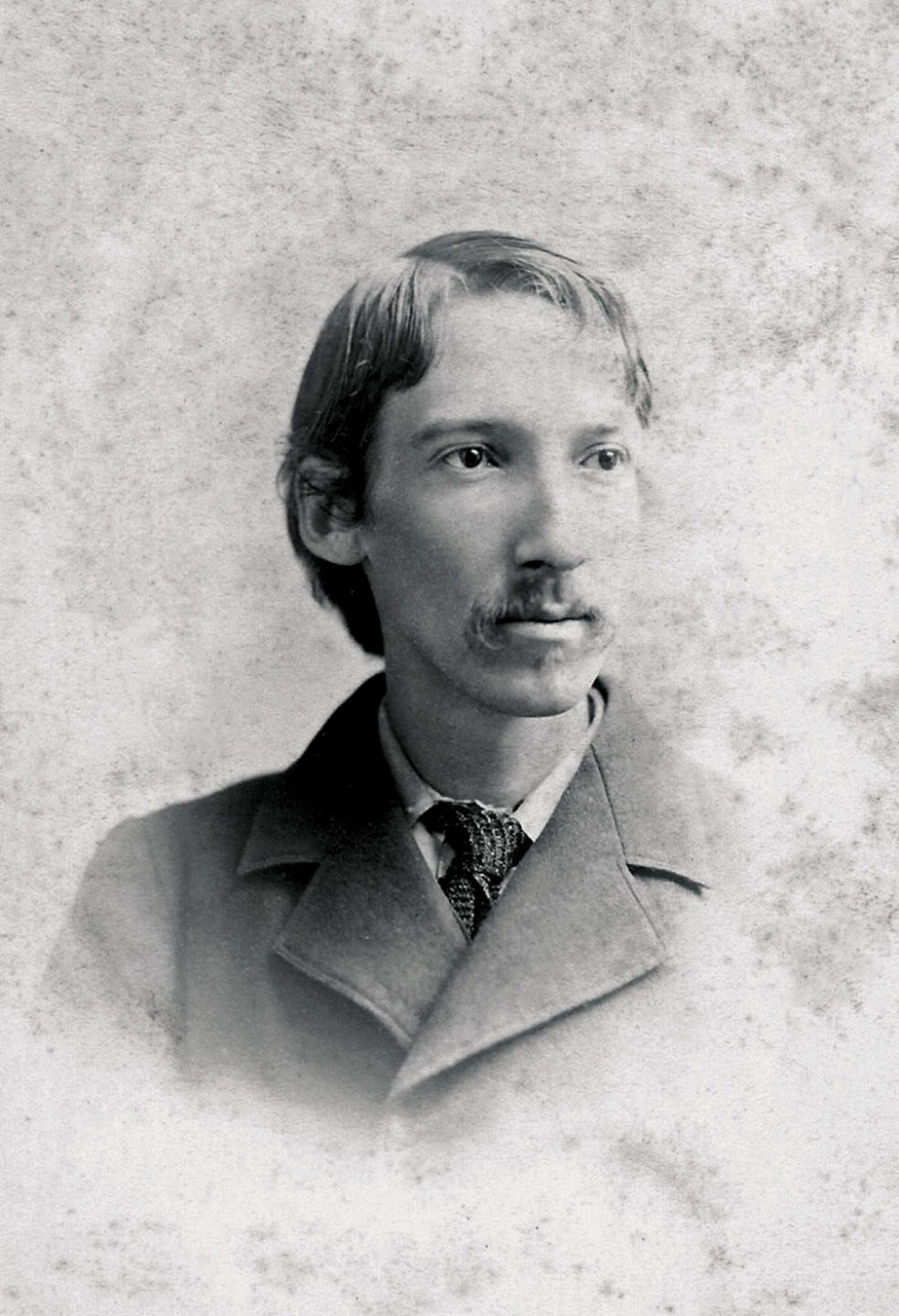

Robert Louis Stevenson lived a short life. He died at the age of forty-four, having spent much of his life fending off a chronic bronchial illness. Throughout his childhood and adolescence he was thin, and as a man, he was rangy and gangly. Stevenson often let his hair grow long and enjoyed frequenting pubs and brothels. At even the most casual affairs, he would show up wearing long, Bohemian velveteen jackets. He was an avid traveler and adventurer, as his

health allowed.

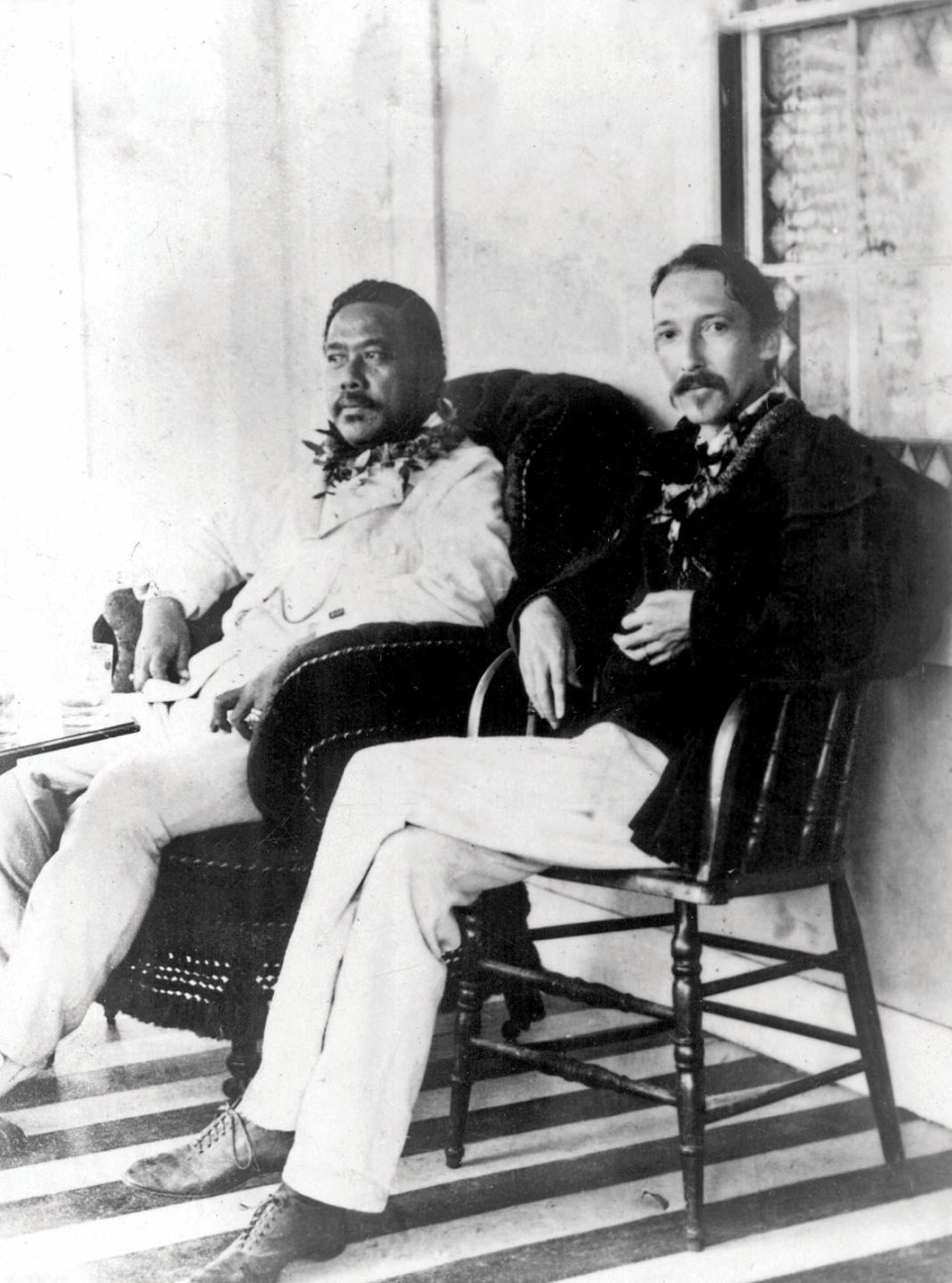

After visiting a commune in the French Riviera to restore his health following a particularly debilitating bout of bronchial illness, he spent time in Paris, where he became enchanted by cultural salons and galleries. From there, he took a long canoe ride through Belgium and France, where, in 1876, he ended up in Grez-sur-Loing, in the Seine-et-Marne. There, he met Frances “Fanny” Van de Grift Osbourne. She was an American, having been born in Indianapolis, and had married Samuel Osbourne when she was seventeen years old. She had two young children but was frustrated by her husband’s infidelities. Still, she remained married for a time. While visiting France with her two children, Isobel and Lloyd, she met Stevenson. They became lovers a year later and spent time traveling through France together. Fanny eventually moved to California, and by 1879, Stevenson followed her there, but not without duress. After a long, second-class trip across the Atlantic on the steamship Devonia, he then traveled by train from New York to California. The trip nearly destroyed his health, and by the time he arrived in Monterey, California, he was near death.